|

Radar Antennas and control unit

GCA control unit

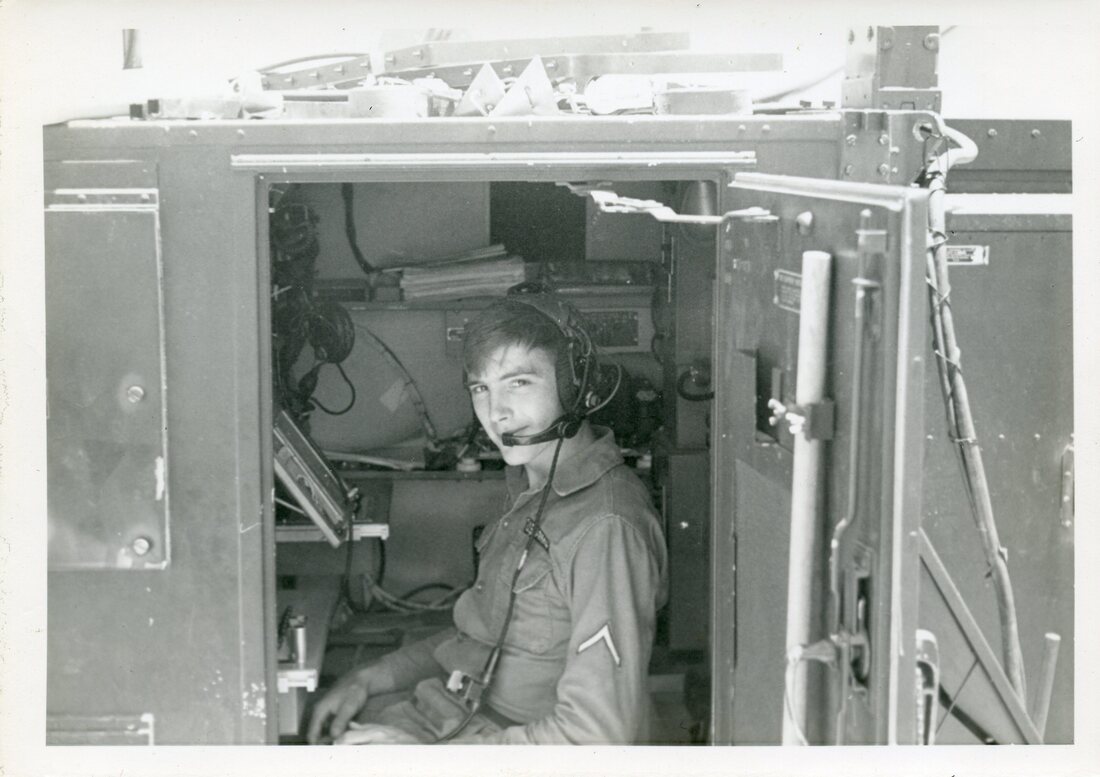

Ernie Camacho manning GCA

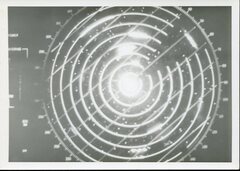

Radar Screen

|

A Night-time Resupply Mission

It was the middle of July, 1967. Dak To airfield had been heavily involved in supporting Operation MacArthur, a major offensive in the Central Highlands against large units of North Vietnamese soldiers. I was the sole radar operator in the small team of air traffic controllers that had arrived at the beginning of this major operation. We had been directing large C130 cargo aircraft bringing in supplies, with more traffic during the days than most major commercial airports. We had also been regularly attacked by the enemy with mortars and occasionally, rockets. One morning I was told that several C130s would be coming all the way from Japan with supplies. They would be arriving at night so that the enemy all around the airfield would have a harder time trying to drop a mortar on them while they unloaded. I, and the rest of our team, spent the day getting ready for this night-time mission. We placed 55-gallon drums along the sides of the runway, filled them up partway with dirt and the rest of the way with diesel fuel. These would be the runway lights. The plan was to have a jeep run around the runway, from one drum to the next. A man holding a road flare would light each one as they drove by. They would do this just before an incoming plane would touch down. After touchdown, they would run the route again, this time with a fire extinguisher to put out the fires in the drums. The less time "Charlie" had to see the runway lights and take aim, the better. I spent the day fine-tuning my radar equipment to make sure it was lined up to accurately guide in aircraft in the dark. The plan here was to have an incoming C130 keep its landing lights turned off until the last minute before landing. Again, this was to give the enemy less of a chance to spot and shoot at the aircraft. My radar unit consisted of a small square-ish enclosure, big enough for two folding chairs, two radar screens, and a shelf of radios. In addition to the enclosure, there were two dish antennas. One went round and round, like you usually see. It scanned an area of about 20 miles radius around the runway. With it I would identify an aircraft by having it make a few turns so I could spot it on the radar screen, then I would direct the aircraft around the airfield until I had it about 5 miles off the end of the runway. Then a second dish antenna, shaped like a banana on end and rotating up and down, would take over, painting a path from that 5 mile, 1000ft high point where the aircraft now was, down a 3 degree slope to the end of the runway. On my radar screen, during the first phase of directing a plane to land, I would have a display just like you'd expect. A line extending from the center of the screen would sweep around in a circle. Anything that bounced the radar beam back would show up as a bright dot on the screen. The second phase, getting the plane from 1000 ft. down to the ground, required a different display. I would switch to a "beta" display that showed two horizontal rectangles on the screen. The top rectangle had a white line going down the middle from left to right. This was the left-right position of the aircraft. The bottom rectangle had a white line that went from top-left to bottom-right in the rectangle. This was the 3 degree glide-slope that would get the aircraft onto the ground. On approach, the two dots representing the aircraft would travel from left to right across the two rectangles on the screen. As I mentioned, I spent the day making sure that these two displays were spot-on, accurately pointing to the end of the runway. Since this was in July, the middle of the monsoon season, we were not surprised when the weather conditions deteriorated later in the day, until by night-fall, we were completely socked in - 100 ft. vertical visibility and maybe half a mile horizontal visibility under the overcast. The good thing was that Charlie would not be able to see us. The bad thing was that normally we would not carry on flight operations with visibility this poor, but five C130s were already inbound from Japan and this was a tactical situation; the mission would proceed. Along around 10PM I made radio contact with the flight group, calling themselves "Kodak" as in "Kodak 12" or "Kodak 20". I don't remember the individual call signs now. I had the flight settle into a holding pattern about 10 miles away, with the planes in a vertical stack, with each plane 1000 ft. above the one below. Imagine 5 airplanes, each one going in a circle, and each one separated by 1000 ft. from the others. After the planes were in the stack, I told the bottom plane to leave the stack and approach the airfield. As soon as he reported leaving, I would have each remaining plane in turn leave their altitude and descend to the next lower level. "Kodak 12, report entering pattern for runway 28". "Kodak 12, entering pattern". "Roger Kodak 12. Kodak 20, descend from 3000, report arriving at 2000". And so on until the stack was re-set. Now I concentrated on the plane entering the pattern. On the rotating display, I'd vector Kodak 12 around: "Kodak 12 turn left heading 180". "Kodak 12, turn right heading 280". I vectored him several times until I had him off the east end of the runway, on a heading of 280 degrees (the heading of the runway). Then I switched to the beta display. "Kodak 12, slightly left of course, turn right 282". "Slightly below glidepath, adjust rate of descent". "On course, on glidepath". I gave the pilot slight corrections to keep him right on the two lines of my radar display. Here I was, a 20 year old kid, with a few month's of air traffic control training at an Air Force base, and a couple weeks training on this particular piece of radar equipment. I had gotten that training about 2 months ago and I had a total of about a dozen radar approaches under my belt. Although I was less than experienced at this, my last few approaches had been very good so I was semi-confident in my ability. I was confident that I knew my equipment, but these were well-seasoned Air Force pilots flying big expensive cargo planes. I suspected that my youthfulness would come across on the radio. All the pilots were listening to everything I said. I was nervous about the difference in rank and how they might not trust me. This first aircraft I was directing did everything right and I was getting more confident that we would pull this off. I had warned the pilots of the poor visibility and low ceiling, so they were expecting to not be able to see anything until the last half-mile or so. I felt that they were understandably nervous too. So, I'm taking the pilot down the glide-slope, "On path, on glideslope, 1 mile from end of runway. On path, on glideslope, 3/4 mile from runway. Slightly right of course, turn left heading 278. Left of course, turn right heading 283". On my screen, the aircraft's dot changed from going nicely along the two white lines to suddenly veering off the path. The door of the radar control "box" opened toward the approach end of the runway. I opened the door to see if I could now spot the C130. I suddenly saw the left wing of the aircraft dipping down out of the overcast. The pilot had lost confidence in me and was trying to find the runway himself. I shouted into my microphone "Pull up! Abort! Go Round!". As soon as my heart slowed down a bit and I knew the pilot was climbing out, I continued, not quite as loud: "Why did you do that? You almost took out our mess tent with your wing!" I went on, knowing all the other pilots were listening: "Listen, I know the conditions are bad. I know what I'm doing. I would have put you right on the runway if you'd stayed with me. I spent all day tuning this equipment to make sure it is good. Let's do this again and this time please stay with me." The truth is, if that pilot had been a little bit more adventurous in his trying to find the field, he would have crashed for sure, probably taking me out since I was right next to the runway. The pilot did not say anything back to me. I was expecting one of the pilots listening would try and put me in my place. I guess they figured my place was right there, with their lives in my hands. This time, I brought the plane around to the approach end, down the glideslope to the runway, and at the end I was saying: "On glideslope, on path. 1/4 mile from runway, turn on landing lights". Again I opened my door to see two landing lights turn on, right off the end of the runway, and just dropping out of the overcast. It was a wonderful sight. About 5 seconds later the pilot was on the ground. As soon as the pilot landed, our guys put out the "landing lights". The plane taxied to the end of the runway, dropped its load, taxied back and then took off. All the other pilots took their turn, each one making a flawless approach and landing. During all this, Charlie was silent. The overcast had definitely helped. When it as all over, I breathed a sigh of relief. I had 5 aircraft, with all their crews, in my hands. If I had screwed up, not only would there have been plane and crew dying, but there were a lot of people on the ground that would have been casualties. Since I did not screw up, it became just another day's work. As it turned out, there were no more night supply missions that I was aware of. But, we continued to break records for aircraft activity at our "Dak To International" airport. -- Ernie Camacho -- |